Houston poses both a typical and an unusual situation for stormwater management. When these intervals are exceeded, and the infrastructure can’t handle the rate and volume of water, flooding is the result. Like bridges or skyscrapers designed to bear certain loads, stormwater management systems are conceived within the limits of expected behavior-such as rainfall or riverbank overrun events that might happen every 10 or 25 years. In other words, cities are built on the assumption that the water that would have been absorbed back into the land they occupy can be transported away instead. The combination of climate change and aggressive development made an event like this almost inevitable.Īccording to my Georgia Institute of Technology colleague Bruce Stiftel, who is chair of the school of city and regional planning and an expert in environmental and water policy governance, stormwater management usually entails channeling water away from impervious surfaces and the structures built atop them. This process-the policy, planning, engineering, implementation, and maintenance of urban water systems-is called stormwater management. To account for that runoff, people engineer systems to move the water away from where it is originally deposited, or to house it in situ, or even to reuse it. But when water hits pavement, it creates runoff immediately.

The natural system is very good at accepting rainfall. In cities, up to 40 percent is impervious.

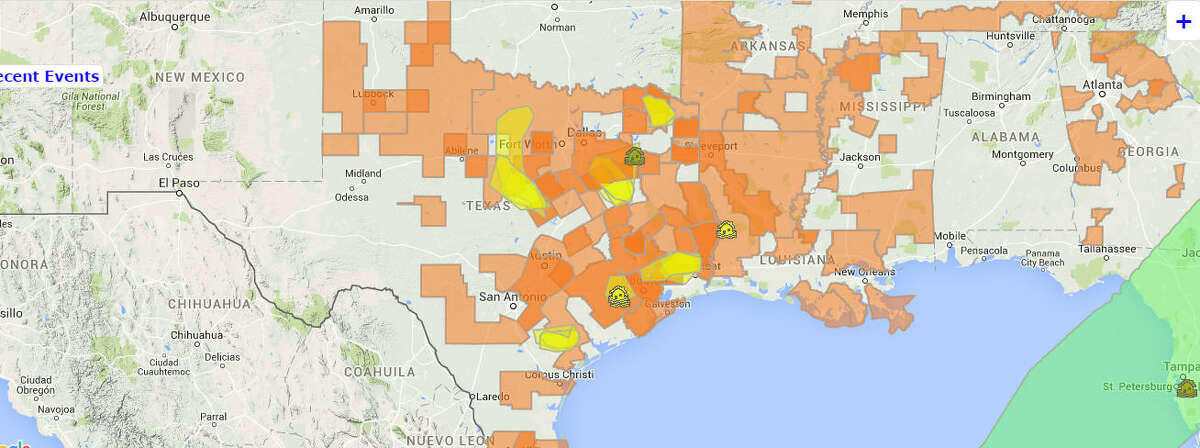

In most of the United States, about 75 percent of its land area, less than 1 percent of the land is hardscape. Roads, parking lots, sidewalks, and other pavements, along with asphalt, concrete, brick, stone, and other building materials, combine to create impervious surfaces that resist the natural absorption of water. And that’s exactly what cities do-they transform the land into developed civilization. The second is covering over the ground so it cannot soak up water in the first place. The ground becomes inundated, and the water spreads out in accordance with the topography. One is large quantities of rain in a short period of time. It gets absorbed by grasslands, by parks, by residential lawns, by anywhere the soil is exposed. Under normal circumstances, rain or snowfall soaks back into the earth after falling. People just don’t tend to notice it until it reaches the proportions of disaster. In truth, flooding happens constantly, in small and large quantities, every time precipitation falls to earth. But all these examples cast flooding as an occasional foe out to damage human civilization. There’s the storm surge from hurricanes, the runoff from snowmelt, the inundation of riverbanks. It’s because the pavement of civilization forces the water to get back out again. The reason cities flood isn’t because the water comes in, not exactly. Those examples reinforce the idea that flooding is a problem of keeping water out-either through fortunate avoidance or engineering foresight.īut the impact of flooding, particularly in densely developed areas like cities, is far more constant than a massive, natural disaster like Harvey exposes. In these cases, the flooding problem appears to be caused by water breaching shores, seawalls, or levees. From Katrina to Sandy, Rita to Tōhoku, it’s easier to imagine the flooding caused by storm surges wrought by hurricanes and tsunamis. Pictures of Harvey’s runoff are harrowing, with interstates turned to sturdy and mature rivers. And Houston’s flood is truly a disaster of biblical proportions: The sky unloaded 9 trillion gallons of water on the city within two days, and much more might fall before Harvey dissipates, producing as much as 60 inches of rain. Floods cause greater property damage and more deaths than tornadoes or hurricanes.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)